Número especial

Sociocultural theory in second/foreign language learning and in the implementation of ICT’s in school contexts

Germán Arellano Soto *

UAM - Azcapotzalco

Con base en la teoría sociocultural (Lantolf and Appel,1994), el modelo de Engeström (2001) es considerado para analizar diferentes autores para proponer un marco de referencia útil para interpretar, desde una perspectiva diferente, los esfuerzos o intentos para implementar proyectos con el uso de las TIC en contextos escolares, explicando porque se lograron exitosamente en unos mientras que en otros no. Se consideran tres aspectos: 1. Diferencias individuales entre los aprendientes de la lengua con respecto a los resultados del aprendizaje. 2. Aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera/segunda a través de los conceptos mediadores del andamiaje la regulación y las herramientas.

Based on sociocultural theory (Lantolf and Appel, 1994), Engeström (2001)’s model is used to analyze different articles found in a review of the literature. Three aspects are considered: 1. Individual differences among language learners regarding learning outcomes. 2. Second/foreign language learning through the mediational concepts of scaffolding, regulation, and tools. Also, the aforementioned model serves as a useful frame of reference to interpret, from a different perspective, attempts to implement ICTs in school contexts explaining why they were successful in some of them and not successful in others.

Introduction

According to Lantolf and Appel (1994), Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory implies that social interaction is the cause of the gradual development of a child’s knowledge and cognition. This development is influenced by the interaction between people and the tools produced by culture. An important element in Vygotsky’s theory is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD is the difference between the actual state of the child (or individual) and the potential state at which he/she can arrive with the help of a more expert one/person. In other words, it is the area of possible growth for which the individual is ready. Lantolf and Appel also explain that after Vygotsky’s death, one of his followers -Leon’tev- proposed a theory that would account for higher mental functions in a different way than Vygotsky had apparently established. Leon’tev’s Activity theory included three levels of analysis: activity, action, and operation.

Activity is defined by the setting or context which is closely related to the motive(s) of the subject. Actions are directed towards a goal. Goals function as a regulator of the activity. Operations determine the way in which the action is carried out (the procedures). A characteristic of operations is that as the individual masters the way of carrying out the activity, such operations become automatized procedures (for example, driving a car). In summary, motives answer the ‘why’ of an activity, goals answer the ‘what’ of such activity, and operations answer the ‘how’.

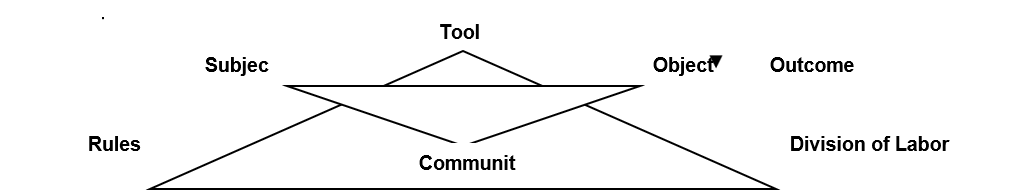

Engeström (2001) explains that based on Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and on Leon’tev’s Activity Theory, he (Engeström) developed a model for the structure of a human activity system. Engeström used the three levels mentioned above, and he included other elements that may mediate the activity system such as community, division of labor, and rules. I will use Engeström’s model (1987) (cited in Engeström 2001) to refer to the different concepts described in this paper (and as illustrated by different articles).

Fig 1. The structure of a human activity system (Engeström, 1987, p.78).

The aim of this paper is to discuss how sociocultural theory, including activity theory, can be a useful framework within which to describe findings from earlier research regarding: a) individual differences amongst language learners in regard to learning outcomes (the subject and the object), b) mediation in second/foreign language learning/acquisition (tools), and c) attempts to innovate with information and communication technologies (ICTs) in school contexts (rules, community, and division of labor).

The subject (and the object)

Individual differences among language learners are reflected in learning outcomes.

According to Engeström’s (1987) model, the upper triangle includes the subject, who is directly related to the object of the activity. In second language acquisition, the way participants (the subjects) orientate themselves towards the task (the object) is directly related to their motives and goals. This has an impact on the way the activity is carried out, as will be illustrated in the following five examples..

1. Students’ backgrounds influence their view of a foreign language

Gillette (1994) conducted a study in which students were identified as effective and ineffective language learners. They had different reasons or goals for second language learning which determined their strategic approaches. In addition, students’ language learning histories made it evident that their social environment was crucial to the way students valued a foreign language or failed to do so. Their backgrounds shaped the way they set different goals (either as a sincere desire to learn vs. an imposed requirement). Gillette explains that life experiences and not schooling are what influence the students’ effort to learn a foreign language, and that students’ values are proportional to their world exposure.

2. Students’ interpretation of the task is different according to their backgrounds

Coughlan and Duff (1994) set out the difference between Task and Activity, referring to the former as a “behavioral blueprint to provide to subjects in order to elicit linguistic data”, while the latter “comprises the behavior that is actually produced when an individual (or group) performs a task” (p. 175). In their study, five examples show how the subjects (one Cambodian and four EFL Hungarians students) interpreted in different ways the same task: describing a picture of a “beach scene”. In the first case, the Cambodian student deviated from the expected pattern by making a dialogue out of the intended monologue. The remaining four examples showed diverse interpretations of the same task such as (2) as a visual memory exercise by describing the things he saw; (3) relating the picture to a film (Jaws) and to a tourist spot (Greece); (4) relating to a hypothetical setting (California); and (5) relating to the subject’s personal experience (Lake Balaton, Hungary). These five examples show how each subject viewed the same task differently according to his/herinterests and experiences.

3. Valuing the language doesn’t mean engagement in the task

Parks (2000) conducted a study with tourism students in an English for Specific Purposes course in a Montreal Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEP). The task was the making of a short tourist video documentary in teams of two. Three participants illustrate the importance of learners’ perceptions in accounting for differences in processes and results of the task. Parks explains that although all three students had a positive attitude towards learning English, their motives influenced how the goals were formulated (either as an assignment vs. an opportunity to learn). For example, for Annie, the video was a course requirement and had little to offer, and the real world was the only place where she could learn a language. Stephanie had a preference for working alone and considered herself an independent learner avoiding group work. In contrast, for Julie, the video was an empowered image of herself making a link between the video and her best image. Her video was considered among the best in the class. According to Parks, Annie’s case (and Stephanie’s) set a caution: “A generally positive orientation to language learning may not necessarily result in effective in-class use of strategies.”(p. 80).

4. Motives and goals can explain variability in group work

Storch (2004), one of the few studies on pair work, conducted a study in an ESL university writing class. Students worked on three different language tasks: 1) A short composition, 2) an editing task, and 3) a text reconstruction. Four patterns were identified: 1. Collaborative, 2. Dominant-Dominant, 3. Dominant-Passive, and 4. Expert-Novice. Surveys and interviews revealed that participants had a positive attitude toward the task and that 7 out of 8 students preferred group/pair work. However, the perceptions of goals were different. For the Collaborative pair, both students felt their role was “to do their best”. In addition, their goal was to share resources and to complete the task together. For the Dominant-Dominant pair the tendency was to display their knowledge. They were competing rather than sharing. Resolutions were not negotiated, and consensus wasn’t reached. In the Dominant-Passive pair, one of the participants appropriated the task. Questions were usually self-directed. Few explanations were offered, and task completion took a short time. In the Expert-Novice pair, the former attempted to involve the latter by asking him for his opinions and suggestions as well as by offering him explanations. Their roles and goals complemented each other. This study shows that goals and roles determine the activity, not the task type. Attitudes/motives are influenced by learners’ backgrounds. The way individual goals interacted produced different patterns of interaction (sharing goals or deviating from them).

5. Students goals can be affected by cultural contexts

Basharina (2007) conducted a study with students from university students from Japan, Russia, and Mexico using WebCT Bulletin board. The different backgrounds of each group affected the learning outcome and caused three types of contradictions (Engeström, 1987):

1. Intra-cultural. At the beginning students had feelings of uncertainty and inadequacy as well as a sense of incompatibility with respect to technology and proficiency.

2. Inter-cultural. Mexican and Japanese students didn’t like the fact the Russian messages were too long, culturally specific, too academic, and impersonal. Mexican students didn’t like Russian students writing their messages before-hand and accused them of plagiarism.

3. Technology-related. Students felt overwhelmed by the quantity of messages posted. The bulletin board was considered slow, and students expressed preference for chatting.

Students were involved in different activity systems, including their local classrooms, the online global community, and their local cultures. Their intra-cultural contradictions resulted from their local activity systems since they represented assumptions and beliefs from prior to the project. These contradictions resulted from the three groups having the same task –online telecollaboration- but being engaged in different activities characterized by their object/motives and mediating tools.

In summary, according to Activity Theory, the participants took a different approach either towards learning a foreign language or accomplishing a task. Such differences depended on their motives, goals, beliefs, and backgrounds. This represents two points in the Engeström model (subject and object). Now we turn to another point on the model.

Mediation

Mediational concepts of Activity Theory (Scaffolding, Regulation, and Tools) can give new perspectives with regards to foreign/second language learning/acquisition processes. Mediation can explain how the interaction between learners takes place and how help is provided, and learning/ knowledge is appropriated.

Scaffolding

Scaffolding is a metaphor that explains how a more expert one/person provides help to a less expert one in order for the latter to increase in knowledge, as if climbing little by little an imaginary scaffold (Werstch, 1979a). The concept of scaffolding can be applied to second language learning since the teacher (the speaker with more expertise) can provide linguistic aid/knowledge to the student (the one with less expertise). Furthermore, students can help each other in building a second language by providing mutual help. For example, Donato, (1994) conducted a study with university students of French in the USA. Using a microgenetic analysis (Wertsch and Stone, 1978), he observed how students helped each other for oral activities. The first protocol shows how three students contributed in order to arrive at the phrase Tu t’es souvenu (you remembered). Students worked together to find the reflexive pronoun te and the proper auxiliary es. The three students were experts and novices at the same time and by combining their individual abilities, they made the task easier, arriving together at the correct construction of the phrase. In the last protocol, one of the speakers requested assistance from his peers to form the phrase in French “If he tells her the truth, she (his wife) will divorce him”. Peers provided scaffolding by offering key phrases that disinhibited his linguistic processing. Together they came up with the correct verb forms and words to form the final phrase which was accepted by all.

In another study, Meskill (2005) shows how computers can serve as tools helping in the process of scaffolding. She describes the work of an Elementary School teacher, Mrs. M, who teaches English to non-native children. Using the computer to support her work, Mrs. M used three strategies (Triadic Scaffolds) to teach language. They are: 1. The teacher’s verbal strategy (i.e. directing, echoing, thinking out loud, etc.). 2. The contribution of the computer (i.e. providing a referent, motivating attention, etc.). 3. A combination of what the first two accomplish (i.e. attention given to form and meaning, lexical acquisition, spelling, etc.). In the process, the children learn sociolinguistic rules of behavior as well.

The learners’ linguistic acquisition through scaffolded help is noticeable, since the language routines they learn in Mrs. M’s class enable them to understand (and eventually participate) in their other classes.

Regulation

Thorne (2003) explains that the way individuals access information to regulate their thinking is developed in three sequences: a) object-regulation (artifacts regulate or afford cognition); b) other-regulation (mediation through a more expert one/person); and c) self-regulation (the individual can perform with minimal or no external help). The process of regulation can be seen in second language learning either through appropriation of the writing process or vocabulary and pragmatics. The following studies illustrate how students learning a second language and using electronic communication go through a process of regulation.

Parks et al. (2005) carried out a study in a Quebec French-speaking High School housing a special program called New Technologies in an ESL language arts class. Grade 10 students were to create a Web site featuring the history of the theatre. The appropriation of the writing process went from other-regulation to self-regulation. This process started back in Grades 7 and 8. Grade 7 students had to create a pamphlet on how to use the dictionary in English. The teacher provided scaffolding through the use of tools such as interpreting dictionary entries, providing outlines, focusing on organizing computer files, etc. (object-regulation) as well as feedback (other-regulation). In grade 8, students organized an imaginary trip to Vancouver. The project went from researching factual information on the Internet to exchanging texts for peer electronic feedback (on content).

Students went through a process of other-regulation to self-regulation by making the writing process their own, since the knowledge and abilities they mastered in grade 10 were new and unfamiliar in the previous grades. They were able to transfer this process to other courses, indicating how important it was considered for achieving better results.

Chung (2005) provides another instance of regulation with three types of Korean students in Canada (‘second generation’ Korean-Canadians, Koreans who had immigrated at elementary age, and Korean visa students). Examining synchronous CMC exchanges, she found that students appropriated language practices, for example, the use of Korean honorific discourse. Knowing the age of the interlocutor was important in using the appropriately respectful forms of address to avoid sounding rude. Initially, the English-speaking students didn’t use such forms and were considered rude by the Korean-speaking students. Gradually, through mediation with peers, Canadian-born students came to address the others in a meaningful way using appropriate speech/honorific forms dependent on context such as Onnie (‘older sister’) or Sunsengnim (‘teacher’).

Tools

Tools are the artifacts by which cognition is mediated and eventually achieved. They can be physical (e.g., books, computers, and Internet) or they can be psychological (e.g., language, dialogues, concepts, etc.). According to Lantolf and Appel (1994), “Tools function as mediators, as instruments which stand between the subject (the individual) and the object (the goal towards which the individual’s actions is directed).” (p. 7). The concept of tools can be useful to explain how learners mediate cognition to facilitate the second language learning process. Tools can enhance the learning process and students may use a variety of them without even noticing it. We can see this in two instances:

Swain (2000) considers the role of output as a linguistic tool in collaborative dialogue. Collaborative dialogue is used to mediate understanding and solutions in second language learning. For example, two students in a Grade 8 French immersion program realized they didn’t know how to produce a sentence (while trying to produce it). They tested their hypothesis and used the dictionary (a tool). Their collaborative dialogue was language-learning mediated by language (a semiotic tool). Swain mentions a study conducted by Holunga (1994) including three groups. The first two were taught four metacognitive strategies: predicting, planning, monitoring, and evaluating (Brown and Palincsar, 1981). Group one was instructed to talk such strategies through (out loud) as they carried out the task. The second one carried out the same task but without verbalizing the strategies. The third one had no such strategies, nor verbalizations. Tests included discrete items and open-ended questions. Group 1 was superior in all tests. Group 2 had significant gains in discrete items. Group 3 had no improvement in any of the tests. Swain explains that according to Talzina (1981), external speech mediated language learning. Dialogue mediated their co-construction of strategic processes and of linguistic knowledge. Swain indicates that in examining the students’ dialogues, she noted instances of language related episodes (LREs) (Swain and Lapkin, 1995; 1998), where language is the focus of attention, and the dialogue mediated learning.

Thorne (2003) shows another example of mediation with tools, since he argues that Internet tools are culturally embedded, and as such they play a role in communicative contexts. He describes three cases (dealing with university students from France and the USA) in which the cultural use of such tools either afforded or constrained communication. In the first case, The Americans had ready access to Internet and used it a great deal, both academically and socially, unlike the French. The former sought a relationship of trust and the building of a relationship, much as they would do with their US peers. The French seemed to favor dispassionate presentations of truth and fact. The messages from both groups were marked by different discourse styles and there were ‘clashes of expectations’. There was exchange but no relationship building. The activity was different for each group since the tool was used differently.

The second case deals with Kirsten (an American student) and Olivier (her French key-pal). They were communicating through e-mail, but she was very disappointed, since he wouldn’t write, and the relationship was almost dead. Then suddenly, he changed to Instant Messenger (IM) and the relationship picked up. From Kirsten’s side, there was linguistic improvement (concerning the prepositional system), and pragmatic improvement, (use of tu/vous), indicating a process going from other-regulated (Olivier) to object-regulated (her grammar books) to self-regulated (her increased competence). The cause for such improvement was the change of tool from e-mail to IM. Thorne explains that though e-mails allow for personal crafting, it’s becoming an outdated tool and that synchronous IM (in Kirsten’s case) accelerated intimacy, idealization, and infatuation. In the third case, during the interviews, three American girls expressed their preference for IM. They wanted to interact using the “right tool”. E-mail was not suitable with age peers, and it was a constraint on the process. E-mail interactions fell flat and didn’t enrich the exchange, so the chosen tool (e-mail) was found to be inappropriate for age-peer relationships.

These articles show how mediation through scaffolding, regulation, and tools aided in knowledge construction and acquisition in second language learning. In many such cases, computers (as technical tools) helped in the process. Other studies also show how computers and online resources can either be used efficiently or inefficiently, whether in second language learning or in other educational settings.

Innovating with ICTs

Trying to innovate traditional teaching by implementing the use of ICTs sometimes results in success, and other times such a change does not seem to be welcomed, resulting in a failure to establish such technologies. Activity Theory can help explain why innovation with ICTs is hard to implement in traditional school systems where incompatible patterns are already established. Engeström (1991) uses his model, which exemplifies an activity system (AS), to explain how all of the components are interrelated. Considering the lower part of his model, it contains three elements that are part of an activity: a) the community (the group of individuals who have the same goal in an activity); b) the division of labor (the way responsibilities are shared or taken by these individuals); and c) the rules (which determine how the activity is to be accomplished). The interrelationship between different activity systems will determine the success or failure of innovating with ICTs in school contexts.

For example, we can refer to Warschauer (1998), who conducted a study at Millers College, a conservative Christian institution in Hawaii. The religious values and discipline of the Church (which sponsors that College) are an integral part in the lives of the students, teachers, and personnel at that institution. Ms. Sanderson’s ESL class reflected the discipline of the college. There was a great number of assignments and she appeared to exercise a lot of control. Computer technologies were used basically as a tool for drilling grammar, and they emphasized form rather than meaning. Essays weren’t very creative. Students were dissatisfied with all the busy-work.

From a sociocultural point of view, this can be understood as three embedded activity systems. The first one would be the Church. In general, the rules are obedience and loyalty to the Church and to the commandments. The division of labor is very hierarchical, and autonomy is not promoted. Also, the community is expected to be faithful to church authority. The second AS is Millers College. Its organization and mission were designed to support the Church with parallel principles such as obedience, faithfulness, etc. Church and college values were reflected in Ms. Sanderson’s class, the third AS. Her emphasis on discipline, order, and behavior (the rules) is congruent with the college’s mission of developing obedient servants to the Lord. Division of labor was hierarchical (with her in control). Autonomy and creativity seemed to be at odds with such a mission. The implementation of ICTs in a more creative way in her class wasn’t possible since the rules, the division of labor, and the community would have had to change, and, the existing AS in her class would have had to change. This would have been somewhat difficult due to the sociocultural constraints from the church and the college as well as from the conservative expectations of colleagues (the community).

An opposite experience with implementing technologies is told by Parks et al. (2003) in a Quebec High School that hosted a special program called “New Technologies” (NT). Students worked with laptops in small groups. They were individually connected to Internet and had different electronic resources available in the classroom. They also owned their computers and had access to Internet at home. Interviews with three teachers reflected a sociocultural perspective in their teaching. Lucie didn’t believe in traditional schooling and her vision was that of a community of learners. For example, her students chose the theme of space, and each group made a Power Point presentation of their projects which ended up being presented in a museum. Mark’s pedagogy focused on the process, and he wanted projects to be challenging. One of them was the production of a Web site. Normand believed in pushing the students to achieve a standard of excellence, as well as in having students learn through project work.

Using the model mentioned, the authors explain that the boundaries of traditional schooling were challenged or crossed in the following ways: The community was no longer one of teacher and students since it extended to other audiences (i.e. museum visitors or Internet users). The division of labor changed because teachers now acted as guides rather than as distributors of facts. The rules placed an emphasis on the process and in the development of work ethics and autonomy rather than on just the accumulation of facts. In addition, teacher’s personal initiatives were not hindered by institutional forces (a second AS) since they were working towards similar goals afforded by three factors: sharing pedagogical goals of NT; having students selected for the program; and being involved in the pedagogical design of the program. Furthermore, all these pedagogical innovations were supported by the reforms of the Ministry of Education (a third AS) based on socio-constructivist principles. Furthermore, the students’ agency was emphasized since they were producers of artifacts rather than just consumers of them. There was a preference for electronic tools, thus increasing their electronic competence. The division of labor was challenged since four types of collaboration were identified: Joint, parallel, incidental, and covert. We can see that ICTs were successfully implemented, since the different activity systems shared intersubjectivity and supported the use of such technologies. In other words, had the school not supported the use of computers through its NT program, it would have been more difficult for teachers to achieve success.

A contrasting example of how ICTs can either be successfully or unsuccessfully implemented (even within the same institution) is offered by Bracewell et al. (2007). A very well-equipped elementary school with ICTs had 6 graders (the Technobuddies) trained in order to help with an increasing need for technical support and maintenance. The program was well received. The authors believed the success of the program was due to the existence of a similar program called the Reading buddies in which 6th graders read to first graders. A program like Technobuddies would have been harder to implement in a traditional school.

A second project within the same school was intended for the development of a professional program for teachers. This project was designed to promote interest in the use of ICTs instruction. Despite the inclusion of many favorable and important elements such as money, expertise, etc., it never got off the ground. Differences came up when the two systems were compared, the existing one and the envisioned one. In the former, tool mediation is deficient; the division of labor has a gap between experts and novices; and the rules are: ‘work alone/conceal’. The envisioned one considered enriched mediation, reciprocal sharing of expertise, and visibility of interest and competence. The authors explain that whether a change is adopted depends on similarity with existing practices.

We can see that in the first case the previous existence of an Activity System similar to the one intended favored the adoption of the latter since the divisions of labor (such as delegating responsibilities to students) were parallel in both systems. The community also shared the same purpose in both situations. In a second case study (dealing with a private K-11 school), despite the support and resources invested in ICTs, these were either used very little or used for drill or practice activities. In interviews, teachers identified four challenges hindering the integration of ICTs into their practices: 1) the need for more professional development; 2) Time constraints of mastering and implementing ICTs; 3) lack of adequate technical support; and 4) classroom management). The authors considered the first three as “perceived” since such supposedly missing conditions were there. The 4th challenge was considered real, since there were greater possibilities for students to get distracted playing games or surfing the Internet (causing a lot of class disruptions). In addition, the expectations for interaction (the new rules), if not met, could cause the students to be alienated from ICTs. The expectations for collaboration (the division of labor) would be difficult to achieve for example if students hadn’t been trained in cooperative learning. The expectations concerning students’ output (the outcome) could be frustrating for them if they didn’t produce a great deal. The authors explain that in order to deal with the challenges mentioned, teachers draw on their traditional practices of division of labor and rules. ICTs create contradictions between the existing division of labor (the way of working with ICTs in the classroom) and the rules of interaction for academic work (Park et al., 2007). So, a redefinition of both is required. The problem is not with ICTs but with the division of labor and rules. The authors conclude by saying that change will only happen if teachers and administrators see these contradictions and resolve them by enlarging their practices concerning the division of labor and rules into a constructivist pedagogy.

Conclusion

Sociocultural theory seems to be used most frequently as a framework to explain how learning and interaction between learners takes place, more particularly in second/foreign language studies. Taking into consideration this theory, I have discussed how activity theory can be used as a frame of reference to interpret (and understand in a different way) the results from earlier studies concerning issues related to individual differences amongst language learners regarding learning outcomes, mediation in second/foreign language learning/acquisition, and attempts to innovate with ICTs in school contexts.

I began by talking about the way language learners orientate themselves towards a given task along with individual differences concerning their outcome. Their different orientations are guided by their goals and motives, which are usually the product of different backgrounds and life experiences. I continued by discussing the way mediation can account for improvement when learning a second/foreign language. More specifically, I illustrated the way learners (and teachers) can provide guided support similar to scaffolding; the way students appropriated the writing process as well as vocabulary and pragmatics going from a process of other-regulated to self-regulated, and the way collaborative dialogue served as a tool for language learning, as well as how the Internet tools, as cultural tools, can afford or constrain language learning. Lastly, I discussed different classroom situations in which the implementation of ICTs was successful in some cases and unsuccessful in others. The sociocultural conditions surrounding the classroom setting such as the institution (and/or its sponsor) or the existence of parallel practices can play a very influential role in determining the success or failure of such innovations.

Referencias

Basharina, O.K. (2007). An activity theory perspective on student-reported contradictions in international telecollaboration. Language Learning and Technology, 11(2), 82-103.

Bracewell, R. J., Sicilia, C., Park, J., & Tung, I-P. (2007). The problem of wide-scale implementation of effective use of information and communication technologies for instruction: Activity theory perspectives. AERA. McGill University. Montreal.

Brown, A. and Palincsar, A. (1981). Inducing strategic learning from texts by means of informed, self-controlled training. Topics in Learning and Learning Disabilities, 2, 1-17.

Chung, Y., Graves, B., Wesche, M., & Barfurth, M. (2005). Computer-mediated communication in Korean-English chat rooms: Tandem learning in an international languages program. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 49-86.

Coughlan, P., & Duff, P. (1994). Same task, different activities: Analysis of SLA task from an activity theory perspective. In J.P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 173-191).

Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J.P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskiain approaches to second language research (pp. 33-56). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by Expanding: an activity-historical approach to developmental research (Helsinki, Orienta-Konsultit).

Engeström, Y. (1991). Non scolaie sed vitae discimus : Toward overcoming the encapsulation of school learning. Learning and Instruction, 1, 243-259.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 2001.

Gillette, B. (1994). The role of learner goals in L2 success. In J.P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskiain approaches to second language research (pp. 195-213). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Holunga, S. (1994). The effect of metacognitive strategy training with verbalization on the oral accuracy of adult second language learners. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto (OISE), Toronto.

Lantolf. J. P. & Appel, G. (1994). Theoretical Framework : An introduction to Vygotskian approaches to second language research. In J.P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskiain approaches to second language research (pp. 33-56). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Meskill, C. (2005). Triadic scaffolds: Tools for teaching English language learners with computers. Language Learning & Technology, 9(1), 46-59.

Park, J., Bracewell, R. J., Sicilia, C., & Tung, I-P. (April, 2007). Understanding and modeling contradictions in a technology-rich, constructivist classroom: A CHAT perspective. Paper presented at the annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Parks, S. (2000). Same task, different activities: Issues of investment, identity and use of strategy. TESL Canada Journal, 17(2), 64-88.

Parks, S., Huot, D., Hamers, J., and H-Lemonier, F. (2003). Crossing boundaries: Multimedia technology and pedagogical innovation in a high school class. Language Learning and Technology, 7(1), 28-45.

Parks, S. (2005). “History of theatre” web sites: A brief history of the writing process in a high school ESL language arts class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14, 233-258.

Storch, N. (2004). Using activity theory to explain differences in patterns of dyadic interactions in an ESL class. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 60, 457-477.

Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97-114). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: a step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 16(3), 371-91.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (1998). Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students working together. The Modern Language Journal, 83, 320-328.

Talyzina, N. (1981). The psychology of learning. Moscow: Progress Press.

Thorne, S. (2003). Artifacts and cultures-of-use in intercultural communication. Language Learning & Technology, 7(2), 38-67.

Warschauer, M. (1998). Online learning in sociocultural context. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 29(1), 68-88.

* Germán Arellano Soto: Profesor-investigador adscrito al Departamento de Humanidades de la División de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades de la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Azcapotzalco. Licenciatura en traducción e interpretación (Inglés -Español) de la Universidad Brigham Young (Provo, Utah. E. U.A.). Maestría en Lingüística Aplicada de la Universidad de Montreal (Montreal, Quebec. Canadá). Doctorado en Lingüística Aplicada (concentración en didáctica de lenguas) de la Universidad Laval (Quebec, Quebec. Canadá). .